Somerset’s case

The case of Stewart v Somerset (1772) is a landmark decision in the long road to the abolition of slavery. James Somerset was a slave who escaped from his master, Charles Stewart. Once Somerset had been recaptured, he was imprisoned on the ship Ann and Mary captained by John Knowles. Somerset had been baptised a Christian on his arrival in England in 1769 and his three godparents applied to the Court of King’s Bench for a writ of habeas corpus. This action was a remedy used in cases of alleged unjust imprisonment, compelling the custodian to bring the individual to Court to determine whether the detention was lawful. Knowles responded to the writ of habeas corpus and the case was heard by Lord Mansfield (a member of the Inn). A further Lincoln’s Inn connection was Somerset’s counsel, Francis Hargrave, a young barrister, in the case which defined his career. Mansfield delivered his judgment on 22nd June 1772.

Mansfield ruled that Somerset must be set free. His decision was based on the conviction that slavery was such an ‘odious’ condition that it was not compatible with the English Common Law or natural law and could only legally exist if Parliament had expressly established it. There was no such Parliamentary provision and therefore no legal justification for keeping anyone as a slave in England.

Before reaching this decision, Mansfield had been unwilling to give a judgment which could have an adverse impact on an economy which derived considerable benefit from slavery and he made repeated attempts to persuade the parties to settle and thereby avoid a judgment.

The issue in Somerset’s case was also on a much narrower point than its subsequent reputation suggests. The issue decided in the case was whether a slave could be detained in England and transported back to the plantations.

Despite Mansfield’s unwillingness to decide the case and his subsequent attempts to emphasise that his judgment was on a narrow point, Mansfield did see it as a fundamental moral issue. The final words in the judgment were decisive: The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political ; but only positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory : it’s so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England ; and therefore the black must be discharged.

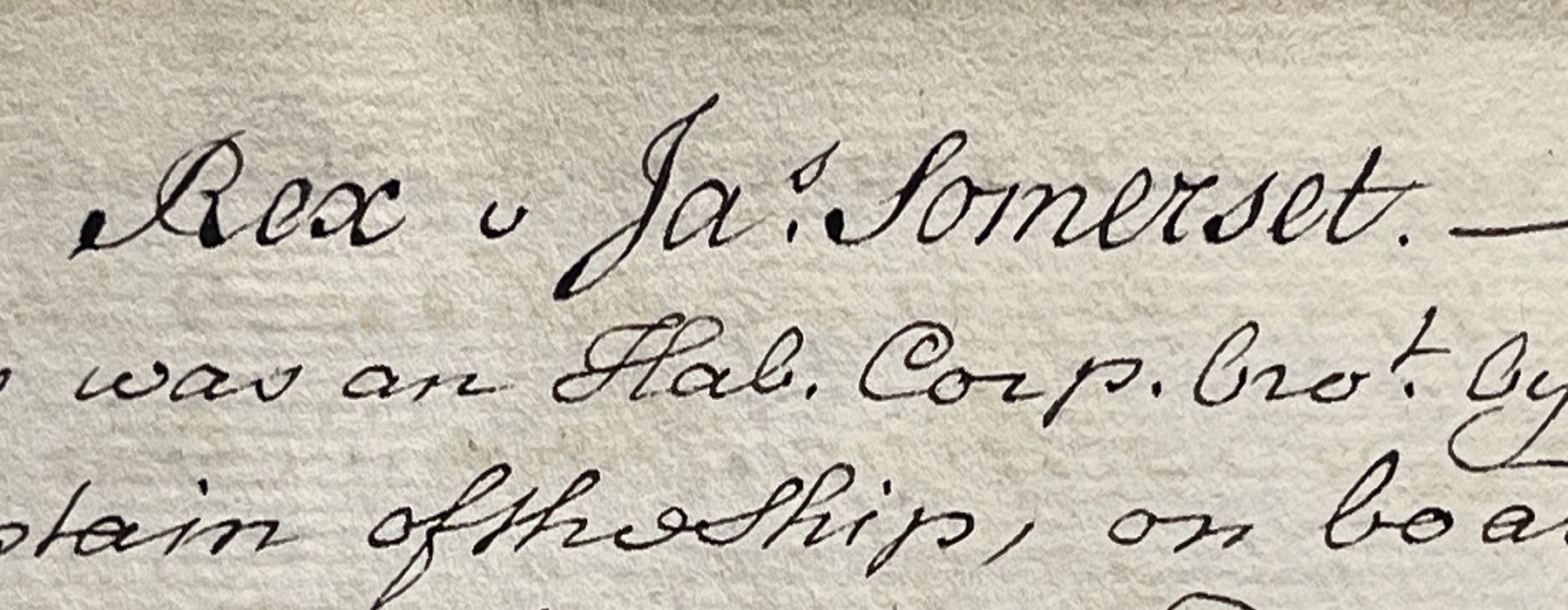

Not surprisingly, the case aroused a great deal of interest. The Library contains two contemporary manuscript records of the decision: the pleadings annotated by Sir William Ashurst and the report by Serjeant Hill

Despite Mansfield’s attempts to emphasise the restricted scope of his judgment, it was seized upon by anti-slavery campaigners, including another Lincoln’s Inn member, Capel Lofft, who published the first printed report of the case.